When you begin to take an interest in Japanese culture, you run up against a frustrating number of strange things. Some are literally untranslatable from the original language, and their meaning can only be captured after the nth round of diffused (but admittedly beautiful) metaphors. Others are difficult to make sense of since a mind that is used to European logic is reduced to stagnation in cultural shock. The text that follows will in part be an attempt to normalize all these feelings – an attempt to develop an immunity (even an informed immunity) to the exotic nature of Japanese culture through immersion in the no less exotic art of Takashi Murakami.

Growth development Murakami Japan

Takashi Murakami was born in Tokyo in 1962. His father was a taxi driver; his mother, a housewife. With so much free time on her hands, Murakami’s mum took up handcrafts and creating textiles. Takashi observed her creative process and was gradually drawn into art..

In the first half of the 1970s there was a lot of western painting being imported into Japan, and visiting exhibitions was a highly popular way of spending one’s time. Each Sunday, Murakami’s parents took him to a museum. But not for leisure. Their aim was to give him a trained eye and the ability to think critically; they made him keep a diary of reports on the exhibitions he visited. And if he failed to keep the diary up to date, Takashi was sent to bed without supper. This strict upbringing and discipline gave Murakami the habit of diligence and the ability to think on his feet.

Takashi himself admits that in childhood he found it terribly dull to look at exhibitions in museums. Once, at the age of eight, he had to stand in a queue for three hours – just to get a glimpse of a painting by Francisco Goya. If the exhausting wait was not bad enough, when he saw Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son, he was horrified. The hideous depiction of the Titan pursued the boy in his dreams and shaped his future approach to painting:

Manga anime otaku

But it was a long time before Murakami began painting. In primary school he clearly preferred manga and anime. His parents reconciled themselves to the fact that their son was approaching puberty and stopped forcing him to visit museums to look at art. Instead, Murakami spent his free time in front of the TV. Who wants to do homework when you can watch the latest episode of Ultraman?

(In the form in which it currently exists manga became popular in Japan in the years following World War II and started playing an active part in the world art market in the 1960s. However, there are also mentions of ‘manga’ in early Japanese art. For instance, the collection of engravings by Katsushika Hokusai goes by the name of ‘Hokusai manga: drawings by Hokusai or fantastical drawings by Hokusai’. Japanese cartoons and animation today are a synthesis of national tradition and graphic techniques taken from American comics: an example of ‘domestication’ and ‘Japanification’ of western mass culture following the fall of the iron curtain.)

When he was in seventh grade in school, Murakami’s academic prowess was subjected to another test. For a whole month Takashi was unable to visit school because he had so many fractured bones. He had fallen into a hole and broken his skull and several bones in his right hand. Boredom and being shut up at home in the absence of any motivation to do his schoolwork were just what was needed to turn his love for mange and anime into an addiction. In Murakami’s case, this was geeky obsession. Or, as they say in Japan, otaku.

(Note that in Japan the term otaku - – お宅 – has its etymological roots in expression of respect for other people’s houses. O is a prefix denoting respect and taku means home. Then, in the second half of the 20th century, the word was used to denote amateur photographers who lead a secluded and sociophobic lifestyle, socializing only with a couple of people from their ‘clique’. In modern Japanese slang otaku also carries a negative connotation of fanaticism and obsession of whatever kind. This is not a word that most Japanese wish to hear used with respect to themselves, and some may take it as an insult. The exception, in fact, is members of this subculture or young people who call themselves otaku.)

The almost pathological fascination with Japanese animation went hand in hand with extremely weak academic achievements: Takashi had by this time almost dropped out of intermediate school. But the need to get his graduation diploma kept him attending school until his final year. He had no illusions about his academic level or chances of entering university. However, he needed to put his name down for ‘somewhere at least’ (this was not the western educational system, where you have a gap year to ‘think things over’). Realizing his freedom of choice was limited, Murakami decided to apply to art schools: they accepted you regardless of how many points you had finished school with. At the same time, this gave him good reason to plunge headlong into becoming a real otaku.

As befits a true afficionado of anime, Murakami formed his own set of favourite authors. He was attracted by the sci-fi manga of Katsuhiro Otomo (Akira, Steamboy) and the expressive style of the animator Yoshinori Kanada. It was at about this time that Japanese cinemas began showing George Lucas’ Star Wars. Murakami literally studied the saga from the inside: he sought out videos shot behind the scenes and observed how the special effects in ‘the Empire’ had been executed, imagining himself to be part of the ILM Effects studio.

This was also when Murakami got to know the art of Hayao Miyazaki, who had just brought to the screen his first animated TV series Future Boy Conan. Despite the simple animation that was typical of Miyazaki’s early works, Conan told the story of frightening events in the third world war. Colonization, deaths, and the difficulties of building a new world: this was the post-apocalypse seen through the lens of anime. Murakami was struck by how Miyazaki used the instruments of animation to convey complex emotions and images.

But it turned out that to be accepted for an art university, it was not enoug merely to have a passion for animation and comics: Murakami failed his entrance exams on drawing. He spent the next two years preparing to apply again. Each morning, he woke at 5.30 so as to get to his preparatory school in good time. And after 12 hours of lessons, he would visit his student friends and draw in their studio until midnight, focusing on his true love – animation.

Nihonga ‘bubbles’, Japanese modern art

In the end Murakami was accepted for Tokyo University of the Arts, but at the cost of a compromise. To increase his chances of getting in, he had to choose the specialization where there was least competition: Nihonga, traditional Japanese painting of the 20th century. The unhurried preparation of mineral pigments and creation of soft gradient outlines on washi paper were things he hardly found inspiring. His response was to adapt traditional painting to his own ends: instead of idyllic and smooth landscapes, he depicted carp that seem to have just been pulled from eddies of turbid water. These gloomy images of freshwater fish allude to his childhood memories of fishing on the river with his father.

And in fact Murakami was disappointed and frustrated by the canons that existed in traditional painting. He was convinced that, as a genre, Nihonga held no potential for him – that he would not become a brilliant artist if he worked only in this medium and painted only these subjects. From the point of view of their content, he regarded the Nihonga pictures created by his contemporaries as pale imitations of works by the Impressionists.

(History knows that in fact the reverse was true. ‘Nihonga’ is the name usually given to pictures created from 1900 forwards in accordance with traditional Japanese art traditions; literally, it means ‘Japanese pictures’. The term was first used during the Meiji period (1866-1912) to distinguish works created in a western style (Yoga) from those that continued the traditions of the ancient Japanese schools of painting.

After 250 years of isolation from the rest of the world, in the second half of the 19th century Japan made a series of diplomatic agreements – first with America, thanks to Commodore Matthew Perry, and then with European states, in particular France. Japanese ‘exoticism’ initially penetrated European daily life through small souvenir shops. By the 1870s the fashion for Japanese objects and works of art had inundated Paris. Artists such as Claude Monet and van Gogh put together their own small collections of Japanese engravings. At the same time, they borrowed from ‘Japanese pictures’ figurative techniques and subjects that we today recognize in European painting as marks of Impressionism: planar perspective, the foreshortening of the background, views ‘from above’ or from a ‘peeping’ position, outlined chromatic spots, framed compositions, and observation of changes in nature.)

Things didn’t work out for Murakami with Nihonga (initially), but still he completed his course in this field in 1988. After graduating, Takashi decided to continue studying painting – only now concentrating on art theory. While the academic work which we now know as the dissertation ‘The meaning of the nonsense of the meaning’ (Imi no muimi no imi) was maturing, Murakami tried to understand what he should draw next. Just as he had done as a child, he visited galleries and looked at large quantities of art.

At this time Japan was in its so-called ‘bubble economy’ phase: import of foreign works of art was undergoing euphoric growth. The galleries were full to bursting with imported works of art, and this prevented young Japanese artists from realizing themselves. The ‘new people’ who owned the borrowed millions were ready to pay for (and even pay above the odds for) works of art. Millions of yen flooded into, for instance, paintings by van Gogh. But not into Japanese modern art: the market for Japanese modern art simply didn’t exist.

The situation changed with the emergence of the Japanese artist Shinro Ohtake, who gave Japanese art a new visual language inspired by Neo-expressionism. Ohtake’s method is to synthesize images taken from mass culture, underground music, and the urban scene. Put together from found objects, ticket counterfoils, photographs from different eras, newspaper cuttings, posters, and publications, his assemblages draw our attention to how things and events are recorded in our memories. At the beginning of the 1990s Ohtake had his first one-man show in Tokyo, and, of course, Murakami was there. Murakami was struck by Ohtake’s collages, sculptural objects, graphic art, and paintings that resembled both surrealist art and the frightening realistic works of Sigmar Polke and Anselm Kiefer:

But in Japan there were still no authoritative texts on contemporary artists. So Takashi travelled to New York to see the vast stores of contemporary art there. The highlights of his art cruise were Anselm Kiefer’s Osiris and Isis at MoMa and Jeff Koons’ famous sculpture Michael Jackson and Bubbles. Damien Hirst, Charles Ray, and Andy Warhol were also must-sees, of course. Murakami’s first encounter with Warhol came when he saw Warhol’s paintings of hand-printed dollar notes. But Muramaki was also attracted by art that was less obvious and not so popular, including engravings and studies by the German draftsman Horst Janssen. The latter’s influence was to be especially noticeable in the quivering lines of Murakami’s ‘Arhats’.

So, what was the end result?

Murakami’s early works were a tense period in his career. His substantial knowledge of a great variety of art and his towering ambition were expressed in the form of relatively straightforward statements.

In Polyrhythm (1991) miniature plastic figures of American soldiers made by the toy company Tamiya clamber over a narrow bar of synthetic resin that resembles a minimalistic link by Donald Judd. The title of this work alludes to the music of David Byrne – music which contains polyrhythms taken from African melodies written by tribes during war. In projecting the idea of the exploitation of ‘military exoticism’, Murakami underlines Japan’s sad fate – as a state caught in the grip of the USA following defeat in World War II.

At the beginning of the 1990s Murakami continued reflecting on the side effects of being a nation defeated in war. Takashi’s Sign is one of his first pieces on this subject. Here he worked with the logo of a company called Tamiya which produces sets of plastic pieces used in modelling airplanes, tanks, and other military equipment. Murakami recalled ‘First in Quality around the World’, the company’s slogan, from his schooldays. Even then, the slogan had struck him as absurdly confident and ambitious – like a lot of the messages that were transmitted by Japanese society in the post-war period.

Tamiya’s claim looked especially overdone given that it had clearly taken its red and blue stars from the American flag. You could say this was the first time Murakami had followed the pop art tradition and integrated his ‘brand’ into the identity of a popular company. In the headline he replaced Tamiya with his own name, and to ‘tame’ the stars he changed their colour from red and blue to green/orange – while at the same time commenting ironically on his own artistic diffidence at the start of his career and the Japanese’ collective sense of loss in the post-war period. But it is still more ironic that, after changing the colours of the stars, he, whether consciously or not, also turned to American visual culture – specifically, to Jasper Jones, who ‘annulled’ the American flag by changing its colours or filling it entirely with white.

Incidentally, on the subject of irony. It seems it’s not possible to be a modern artist and not mock what was created before you came onto the scene. Conceptualism gets most of the flak. To make fun of On Kawara’s meditative recording of daily life, Murakami placed a golden star with the date of his birthday ‘2/1’ on an enormous dark-blue curtain. The pretentious dark-blue velvet is the background for a no less haughty, glistening five-pointed star whose proportions recall the stars on the US flag. Starchild (1992) mocks western collectors who try to scoop up Kawara’s paintings – especially those created on their own birthdays.

Murakami created one of his most understated pieces when he tried his hand at abstract painting. In 1994 he painted ZuZaZaZaZaZaZa, a jagged flow of white paint on a bright-crimson background. The apparently random, almost Pollockian splash of paint was in fact an imitation that used the precise forms and ideal outlines of drops of paint. The splash of white is capped by a miniature, long-eared figure wearing a bow tie and white gloves, with a tail that resembles the vestigial lightning of Pikachu. This hybrid of Mickey Mouse and the yellow Pokemon was a prototype for Mr. Dob, Murakami’s comic-book alter ego and avatar.

Passing through numerous iterations (including one coloured Klein Blue), Mr. DOB became an independent character – one of the first in Murakami’s universe. Takashi created the first variant of Mr. DOB with the help of a friend who was just setting out in his career as a designer. After several weeks of extempore studying of Illustrator and Bézier curves, Murakami’s friend got his computer to display the spherical Mr. DOB – with large, excited eyes and pretty eyelashes. The figure’s name can always be found on the figure itself: the ‘D’ and the ‘B’ are inscribed in its round ears, and the ‘O’ is formed by the character’s face. The abbreviation ‘DOB’ refers to the slang Japanese expression ‘Dobozite?’, which translates as ‘why, to what purpose?’. This is another case of Murakami engaging in cynical criticism of conceptualism: his Mr. DOB character includes a still more nonsensical Easter Egg alluding to slang used in Japanese manga.

At the same time, in addition to the humorous context, the intense smile worn by Mr. DOB conveys a kind of anguish that borders on quiet hysterics. ‘Why? To what purpose?’ this character screams through his teeth. He can’t help asking himself how the modern world is ordered, and he can’t help pondering its absurdity, its senselessness, while at the same time addressing all those global symbols of consumerism: Mickey Mouse, Astro Boy, Hello Kitty, Super Sonico, and even Cheburashka. He addresses everything that is his own basis. The new pop idol, Mr. DOB.

Mr. DOB is the lyrical hero of Murakami’s realistic fairy tales. Murakami has integrated Mr. DOB into his works and made him their principal character. As a product of the western pop lexicon and the manga-anime aesthetic, Mr. DOB is the link and binding image that gives Murakami the opportunity to address western culture in Japan, Japanese culture in the US, and the mutual influence of the two cultures.

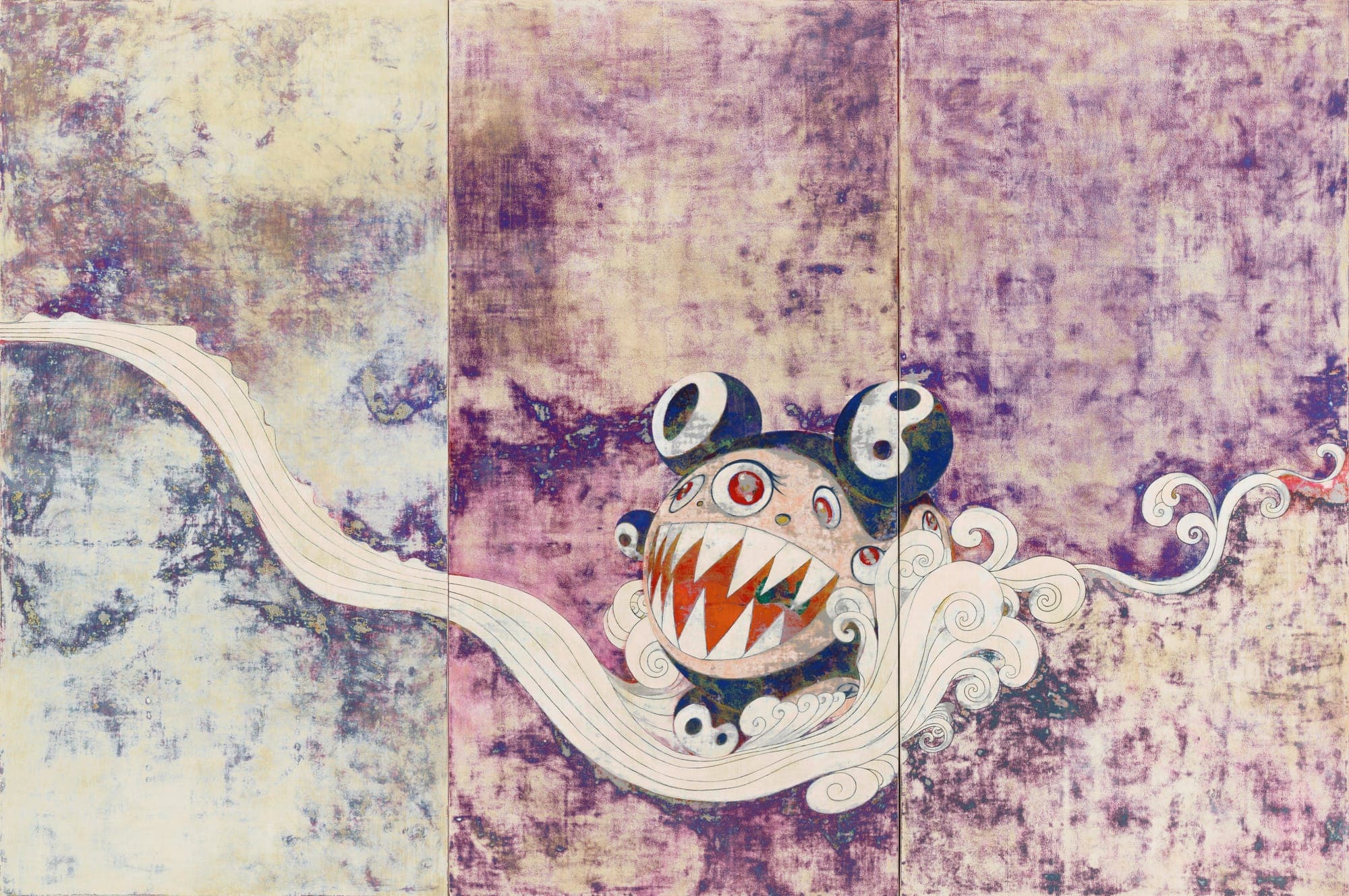

In 727 (1996) Mr. DOB, his gaping mouth full of sharp fangs, comes surfing out onto the surface of the picture on the crest of a wave that clearly refers to Hokusai’s The Great Wave. There seems to be nothing here that could distract you from contemplating the wave: the abstract background, created by scraping off layers of paint, preserves a tranquillity that is characteristic of traditional paintings on Japanese folding screens. But your mediative contemplation of the silk panels is doomed: the process is loudly interrupted by Mr. DOB. By putting digits in the title for this work Murakami tells us why Mr. DOB has mutated into a sharp-toothed monster: 727 is a reference to the American military airplanes made by Boeing that flew over the city of Takashi’s childhood on their way to bombing targets.

Like this mad Mr. DOB bursting into a space formed by half-tones, American mass culture burst into the post-war Japanese mentality, forming a new national identity. Murakami makes no attempt to condemn or resist westernization. Instead, he documents it, studying the ‘Japanification’ of western culture and underlining and fuelling its most contradictory forms.

In the middle of the 1990s Murakami received a grant from the Asian Culture Council and moved to New York. After Mr. DOB’s debut in Japan, Murakami looked for a way of inserting himself and his alter ego into the American art scene.

He began developing the opposite tendency in manipulation of cultures: he tried to Americanize, to organize the export of the images which he knew best of all. In other words, to transform exotic ‘Japanism’ into an attractive product that could be sold on the market in the west. And it worked.

I realized that I, too, was a minority in New York and would need to use my background.

In 1996 he for the first time took part in a group exhibition in the US – at Feature, Inc, a gallery in New York. His third exhibition in this gallery was the first time that Murakami’s works had been available to buy. The same year, Murakami launched Hiropon Factory, a large studio inspired by the tradition of Japanese xylographic factories of the Edo era and, of course, the famous factory established by Andy Warhol. This moment marks the start of a series of parallels between American and Japanese pop art, between Lichtenstein and Murakami, between Warhol and Murakami, and between the numerous Marilyns and the infinite versions of Mr. DOB.