Everyone has a friend like this. He’s always flicking through feeds on social media, saving quotes by famous people or things that are signed with their names. He puts the ones he especially likes on a board of honour – in public view on the main page of his profile – or even uses them as wallpaper on his phone screen.

It seems the done thing for human sapiens, the only surviving representative of his species, to be constantly looking for and finding around him sources of self-identification and self-expression. One such source at the present time is social networks and the Internet. Amid the stream of dopamine released by world news, events in other people’s lives, and other informational noise we can make out something relevant, resonant, hard-hitting, sharp on the tongue, capable of holding our attention. Long enough, at least, to read the text on the picture.

The work of CV HOYO contains big statements that sound like quasi-philosophy of the kitchen-sink variety and mock themselves in the manner of memes. We come across them in his personal online diary, which is, both literally and metaphorically, open for anyone to read. Below, I analyze how he uses memes and clichés to create modern art – and how he manages to talk about serious topics without ever sounding too serious.

On self-identification

What does CV HOYO write about himself? His account in that forbidden network with pictures (i.e. Instagram, which has now been banned in Russia) contains the following laconic bio: ‘international porn star and dyslexic poet’. If we take the first part of this description as an example of the author’s supreme modesty and food for the reader’s imagination, the second, when you look behind the medicinal terminology, is code for the medium used by CB HOYO. In this medium the ‘what’ is words, and the ‘how’ is the specific way in which the words are put together..

CB HOYO was born in 1995 in Havana, the capital of Cuba. In 2013 he moved to Europe. Initially, he found work as a cook’s assistant in a restaurant. To sweat 14-hour shifts at a stove, especially when this lifestyle is not your goal in life, is hardly the most inspiring way of spending your time. The only thing that saved CB HOYO from burnout was the several hours a day he was able to give to creativity. These brief exercises in domestic drawing shaped his desire to do art. To be more precise, they awoke artistic tendencies that had existed in him from childhood.

In an interview CB HOYO has said that he has been surrounded by art for as long as he can remember. As a child, he and his mother would go to exhibitions in traditional museums and modern galleries. He learnt how to draw even before he stopped crawling. He was always drawing and creating something but never took it seriously. Realizing how his life oppressed him and how unhappy he was with it, he took his first step towards ‘art’: he gave up his hateful job. (Curiously, his entire subsequent career as an artist has involved rejecting categories of art or throwing down provocative challenges to the art world.)

Looking for a basis

One day, CB HOYO decided to do the standard artist’s thing (a great way of procrastinating): he left his studio apartment to replenish his supply of art equipment. Paying for his purchases at the cash till, he suddenly thought, ‘Why am I spending so much money on paper for drawing on? Money is paper too.’ It was then he decided to draw right on the banknotes themselves.

The paper basis of the dollar banknote became the basis for CB HOYO’s entire conceptual approach: to doubt the stability and statuses of all definite categories in life. Apparently randomly, CB HOYO started collecting important and precise images. In the spirit of petty art hooliganism, he added silly faces to a portrait of George Washington. This was like Marcel Duchamp – who 38 times drew a thin pencil moustache on an image of Mona Lisa as a way of subverting this work of art’s status as an exemplar of absolute femininity and incontrovertible beauty.

In drawing on banknotes as if they were children’s colouring exercises, CB HOYO annulled this money’s practical function, together with its position in the world economy. The American or Hong Kong dollar, the Thai baht, the Venezuelan bolivar, the Ukrainian hryvna – CB HOYO reduced them all to the same level, turning them into material to sketch on, just ordinary sheets of paper. He replaced measurable prices with immeasurable values, creating new possibilities to talk about money and the place of money in the world order, and particularly in art.

In CB HOYO’s drawn-on ‘Money’, art, in the form of a self-mocking avatar of a smiley, unceremoniously enters into clumsy collaboration with capitalism. Art’s insertion into one of the links in the system mixes up the notions of value and price, unmasking the modern art world, which has mutated into business involving sums that run into multiples of millions. In what respect is this not a metaphor for things that really exist?

Four years later, in 2021, CB HOYO mocked another phenomenon of the modern art economy. His digital work Better burn your money tries, as if entirely seriously, to talk us out of investing in itself. This is a skilful piece of sabotage. As an illustration of a more profitable way to use money, CB HOYO attached to a digital lot on the NFT marketplace Opensea a literally scorched ‘working’ American dollar with a drawn-on flaming tail. By mixing fake and real, digital and physical, CB HOYO sincerely mocked the absurd commotion around and over-consumption of digital art. And yet he was not renouncing participation in the general madness, and the fact that he put this and other works up for sale only added fuel to the fire.

From banknotes to canvases

Still, to spend one’s whole time drawing on real money is painfully bourgeois, especially for an artist at the beginning of his career. The profligate use of banknotes for the good of art got CB HOYO thinking about over-consumption – of material goods, art objects, media, mass culture. Returning to more classical (not to say, more economical) materials, CB HOYO created Faded, a series of sloppily executed canvases in a chewing-gum colour with blurred cartoon images.

This is one of those rare cases where the phenomenon of over-consumption of something is met not exactly with condemnation, but with an expression of dismay at what is happening. In Faded CB HOYO took barely recognizable figures from The Simpsons and Disney cartoon series and caused them to disappear, to dissolve in a pink background – as if hinting that one day everything will disappear, even the most popular images from children’s cartoons, images that have become established as something unshakeable in our minds and daily lives. Between recognizability and commonality, between presence and disappearance, there exist only those values which we cultivate ourselves.

There is no better way to learn skill in painting than to copy pictures by old masters. Or masters that are not too old. As a true self-taught artist, CB HOYO arrived at this thought intuitively, without having to come into contact with academic art education and its copying of the gleams of a vase in a Dutch still-life. He made precise copies of works by Van Gogh, Magritte, Picasso, Bacon, Basquiat, Warhol, and Lichtenstein. In doing so, he investigated the new possibilities offered by painting techniques and materials. Into his ‘copies’ of world masterpieces he inserted his own thoughts; this was like having an abstract canvas by Rothko serve as a page in someone’s personal diary. Without trying to tailor his interventions to their settings, CB HOYO placed his statements directly on top of well-known images and pictures, thus lowering the degree of snobbism and cancelling the effect of breathless veneration with which we usually acknowledge ‘a unique original’.

Fakes was a series of works that became the background for discussion about the value possessed by things that we endow with the status of a masterpiece. Will a fake Rothko work of abstract art have the same effect as the original? Could the endless reproduction of Basquiat turn the original canvases into overrated references? Is it necessary to possess a certain set of ‘canonical’ images to have the right to be called an art collector? Is the possession of imitations of original works of art shameful, senseless, or simply disgraceful? CB HOYO answered all these questions with clear, vitriolic short manifestos that are the opposite of imho (‘in my humble opinion’) – they’re more like the tags used by graffiti writers. He continued the ‘overrated’ theme with reproductions of already well-known works of art: Hockney’s Splash and da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi. This was a way of shifting ‘masterpieces’ into the category of ‘mainstream’.

FAKE IT TILL YOU MAKE IT

After a couple of years’ working with ‘Fakes’, CB HOYO got bored. In any case, any list of modern works of art has a tendency to come to an end – unlike speculation concerning these masterpieces and about art in general.

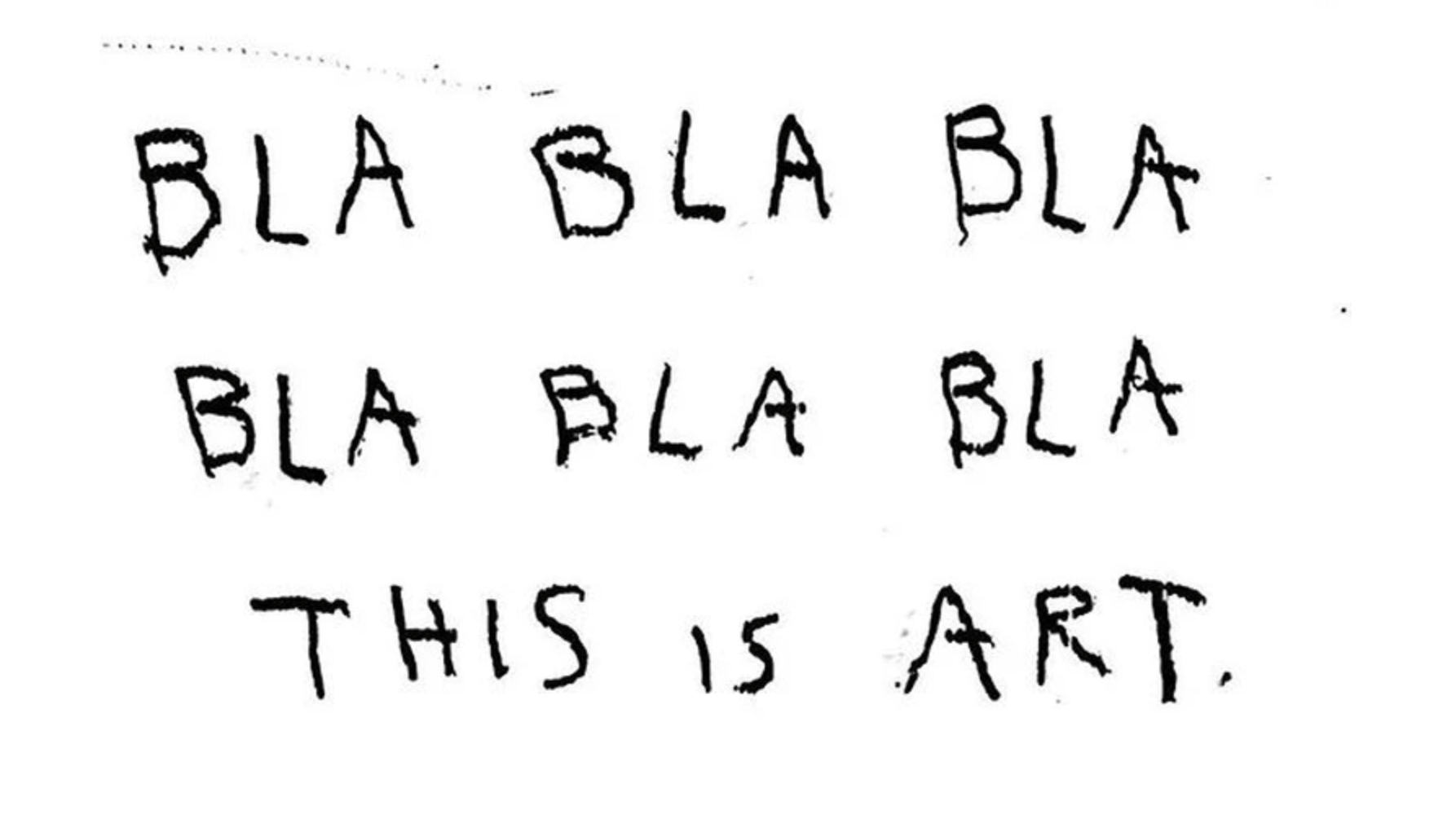

So nothing should distract viewers from his manifesto, CB HOYO needed to clean his canvas. Literally. He now preferred an empty white sheet of paper to a strident pop-art background. This was just an ordinary sheet of paper on which people write different things. One person, for instance, might write the order of the day in black ink. Another, a shopping list. A third, homework for a psychotherapist. A fourth, random thoughts on art. On his sheets of paper CB HOYO puts everything all at once, making public what most people confine to the pages of their private diaries or to notes intended for a limited readership. Frank admissions, existential questions, vulgar jokes, self-flagellation, statements criticizing or doubting what happens in life and art: everything we think about but don’t say.

Historical background

Words are the main medium in CB HOYO’s work. He mixes verbal tools with his own charisma and sarcastic sense of humour. And however much he may have tried to renounce participation in making contemporary art, he uses the language of art (literally language) developed by conceptualism. Keeping his distance from figurative elements as such, he transmits meanings using text and intonations that are automatically turned on in the viewer’s mind when reading/observing his works.

Similar ‘philosophical diaries’, spiced with romantically hermit-like moods (CB HOYO: ‘Nothing is real, Nothing is fake, It’s all relative’), and sometimes direct instructions for life are found in works by the Moscow conceptualist Viktor Pivovarov. See, for example, Pivovarov’s Regime for a Lonely Person and Project for the Dreams of a Lonely Person.

CB HOYO’s short statements in bent neon refer to luminous objects by Bruce Nauman. One of his quotations (‘Don’t wait until it’s too fuckign/ng late’) contains a concealed Easter egg referring to Nauman’s method: CB HOYO has added a pointer to the way the letters in the word have been rearranged exactly as in the palindrome sign ‘Raw/War’, which links words’ formal and conceptual traits.

Now let’s get back to CB HOYO.

‘Shit CH says’ is words straight from the artist’s mouth. It reveals, as if on litmus paper, the most fundamental and at the same time most tabooed thoughts that from time to time pop up in all our heads. Stripped of self-censure, filters, and corrections, these banal but resonant quotations amount to something like the principles of life: axioms for everyday stoicism adapted to the new reality. A philosophy whose entire appearance says ‘anti-philosophy’.

CB HOYO doesn't focus on ‘designing’ his micro-manifestos in some particular way. (OK, yes, he adds colour to his ‘Corny quotes’, heightening still further the ‘childish’ appearance of thoughts that are by no means childish, e.g. ‘Overthinking will fucking kill you’). The boldest things remain absolutely naked: left in a ‘raw’ font as the embodiment of supreme openness and vulnerability. This signature style – free, jagged, a little jerky, not polished or contrived – contains just as much of CB HOYO’s individuality as do the messages in which it is written. What CB HOYO is putting across here is not vulnerability; on the contrary, he is declaring his wishes loudly and directly. This is like reading notes written by a small child who is not able to make himself agreeable to people and makes no attempt to be likeable.

Pretend to be whatever you like

Unlike the false mentality of the social networks in which CB HOYO places his ‘diaries’. At the same time, the audience of the forbidden social network with pictures, clearly already sick of the toxic ‘idealness’ of the idols, is quick to deliver its approval of CB HOYO’s ironic quotations by pressing the heart icons and icons for reposting stuff on one’s own page. (A new form of self-identification that came along hot on the heels of phone-screen wallpaper with ‘Quotations by great people’.)

At the same time, CB HOYO launched a virtual social experiment that made use of his followers’ energy. ‘Wednesday poll day’ was a weekly feature that he published in his account over the course of the pandemic. Asking random, highly unexpected, unpleasant, and sometimes disparaging and strange questions, he asked people to vote for one of two possible answers. The point was to choose a single option without indulging in excessive analysis. For those respondents who were particularly interested, CB HOYO had the following advice up his sleeve:

It is only natural to suppose that for CB HOYO to launch a discussion on digital art was merely a matter of time. After all, what could be more ambiguous or riper for speculation than how NF art has suddenly surged in popularity. WHAT WILL WE DO ONCE THE HYPE IS OVER?, a series of animated objects on the platform Nifty Gateway, tells viewers in no uncertain terms of the dubious prospects awaiting digital art and of the overexcited hype that goes way beyond the quality of the works that are its source. What we periodically glimpse through ‘Also art’ is ‘not art’. And recognizable texts by CB HOYO (e.g. ‘Pump it’) pop like empty air balloons filled with fake currency. Is this not the fall of hype that we have been seeing recently?

For an artist who works with the theme of fakes, CB HOYO produces an extremely small amount of fake news and newsworthy events. On the contrary, some of his statements turn out to be ironically prophetic. WE ARE ALL F*CKED, a series of prints on a black background that CB HOYO created at the peak of the pandemic, reflected the mood of society at that time of great stress. As the pandemic restrictions were eased, people hoped to return to their normal, usual lives, when the situation would be put to rights once and for all. But CB HOYO clearly knew something more. His view was: ‘WE ARE ALL F*CKED. AGAIN’.

CB HOYO is frankly indifferent to other people’s evaluations of what he does. He seems not at all interested in other people’s opinions. He is, it seems, simply joking around the whole time. However, behind this playful aesthetic we can glimpse careful observation of humanity and of people’s thoughts and behaviour.

CB HOYO uses humour and childish aesthetics to offer all of us an investigation into the essence of modern society, that new whimsical normality in which we live today. His equivocal fusion of acidic reflections and naïve allegories is a tool by which he mocks us and at the same time points to the strange rules that guide modern society, to the falsity that permeates this society, and the falsity of the art that is made by this society. But…